Gwen D’Arcangelis

Associate Professor of Gender Studies

Skidmore College

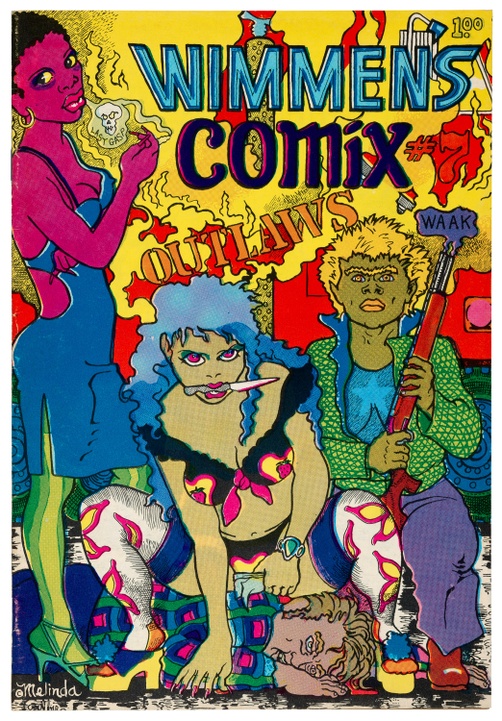

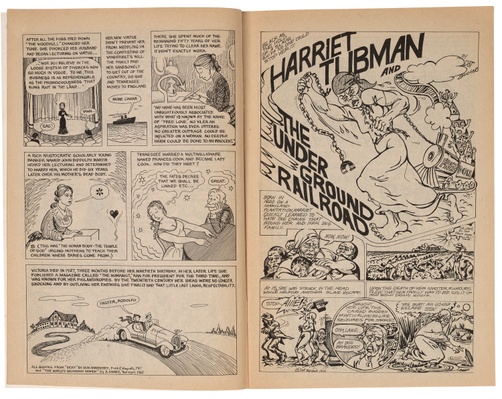

I began reading comics in the early 2000s, when I discovered the feminist, queer-centric Dykes to Watch Out For. Other feminist-inspired comics followed: Fray, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Y: The Last Man. Recently, I discovered another comic: the Tang Teaching Museum acquired issues 5, 6, and 7 (1975–1976) of Wimmen’s Comix. The series, birthed in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1970s women’s lib era, produced seventeen issues in its twenty-year run. Intrigued, I wanted to learn more.

In the introduction to a two-book anthology of the series, cofounder Trina Robbins briefly chronicled its genesis.(1) She described the male-dominated, sexist underground comics scene and how this inspired the creation of an all-women-authored series. Her narrative was accompanied by photos of the collective: they wore 1970s garb and the one man pictured (the publisher) sported a long, untamed beard. All of this triggered my nostalgia for an era I imagined to be wonderfully radical and experimental.

But I noticed something else as well: all eight members pictured were white. This observation kicked in a different type of sentiment—wariness. I was well aware of the particular gaps surrounding race in US feminism in the 1970s. I wondered: were any of the members women of color and, further, how was race portrayed in the comic? The seventeen issues offer a diversity of topics and a range of tones and visual approaches.